Setting Sail

Prose and purpose for a new year

2025. Stay gentle and do not despair. Grieve, yes, fall to the earth; it is the way to the medicine and it will strengthen our defiance. Abandon certainty. Abandon the conflict of opposites. Become immense and do not be afraid to be relentless. Soften and make new visions. We will water the soil with our tears and see what may blossom from our attention to each other, to our collective liberation. Allow catastrophe to give way to unity. In unity comes the balance of all things.

This northern short-tailed shrew was in the middle of the path, nearly still warm. I admire a creature who barely can see and smell, but feels its way through life, spending most of its time beneath the surface. Shrews are venomous, too, uniquely so among mammals. This small being is quiet but mighty. I smiled, placing its clover cap and death adornments, and saying goodbye.

It isn’t because I’m morbid that I’m drawn into a relationship with Death, but because I love this world. I don’t mean “love” as in the way I love soup and Moroccan rugs (so great when they’re great). I mean it relationally, I mean it as an act of deep listening, I mean it as a commitment drawn from the most personal whispers of my interiority. Love that knows Grief and says, “Yes, this too.”

We know about Love, the willingness Love-ing takes to be undone and transformed, to step into an intimate unknown. And Death? Our sacred obligation, the divine payment, our humble surrender to the limits of our being. Death is the anchor that tethers us to this whole operation, buoying every blessing and trouble of the world. “The sooner we can embrace death, the more time we have to live completely, and to live in reality,” says my oft-quoted zen teacher, Roshi Joan Halifax.

To love is to live is to lose. Still, we hungry ghosts move in a cryptic denial about the fact that everything we attach ourselves to will leave us at some point — ourselves included — and we go to great material and psychological lengths to maintain a sense of stability. We stay “productive;” we affix to inherited identities; we narrow our encounters with discomfort; and, in the words of another of my teachers, Francis Weller, we “migrate to the margins of our lives” in hopes of avoiding our inevitable entanglements with loss. In a global and collective sense, too, we seem willing to miss what is right in front of us, swaddled in the amenities of denial and cooed by our own certainties.

Grief, however, is not so predictable. Grief exposes us to the elements. Grief begets change.

Grief tending, then, is a skill; it is how we can honor the vulnerability of Love, the deep risk. So it is that Love and Grief are bound, the watermarks of Mystery herself, painted upon the canvas of impermanence.

Loving and grieving are joined at the hip, for all the beauty, soul, and travail that brings. Grief is a way of loving what has slipped from view. Love is a way of grieving that which has not yet done so. We would do well to say this aloud for many days, to help get it learned: Grief is a way of loving, love is a way of grieving. They need each other in order to be themselves.

— Stephen Jenkinson

From Die Wise

Death is life’s only promise, against which neither hope nor hopelessness is useful. So perhaps both hope and hopelessness are a kind of truancy, a failure to show up to the lesson, to life, to our date with Mystery. Then we see that we don’t need hope to proceed, only a willingness to take up the assignment of our days, namely, to occupy the fact that we were born into an “insanely troubled time,” as Jenkinson would describe it all.

We need a willingness, wonder and curiosity, and a tolerance for the inconceivable. For staying available to the emptiness of not-knowing. For relating within the incomprehensible, blessed web of creation. And because, as I heard the brilliant Ta-Nehisi Coates say in an interview, “[…] we have to guard against the temptation to accept that history is necessarily the limits of who we are as human beings.” But this possibility, let us not hold it hostage to hope.

Brilliantly penetrating, luminous with truth,

She strips away the unreal to show us the real.

This is the true ride — let’s give ourselves to it!

Let’s stop making deals for a safe passage:

There isn’t one anyway, and the cost is too high.

We are not children anymore.

The true human adult gives everything for what cannot be lost.

Let’s dance the wild dance of no hope!— Jennifer Welwood

From “The Dakini Speaks”

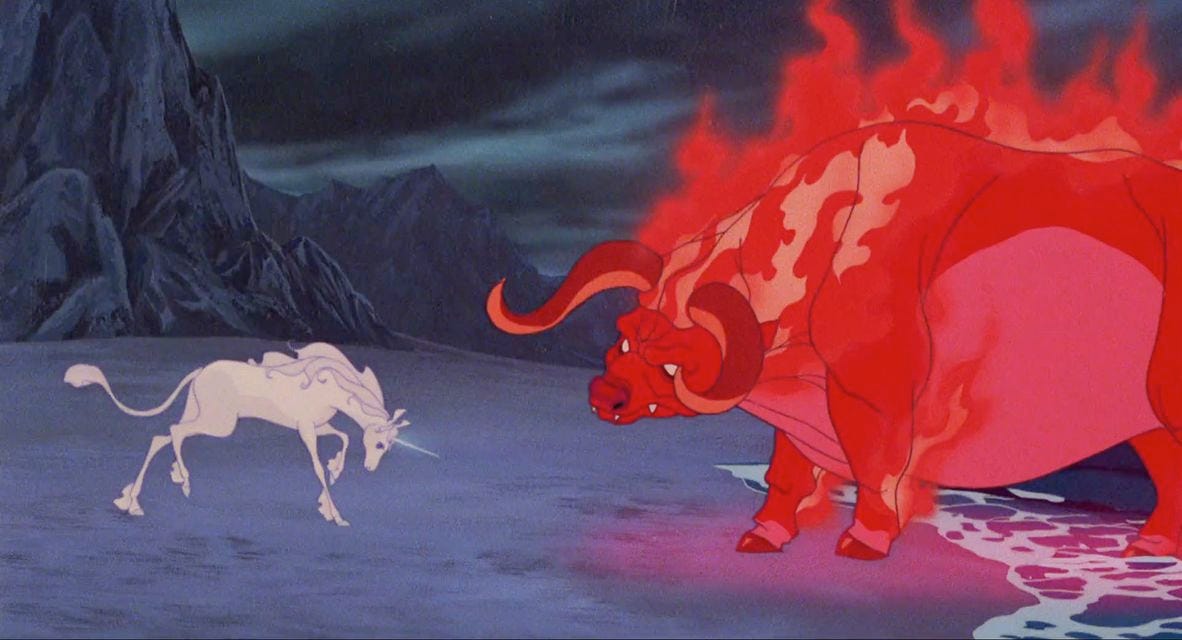

“Death is the tide that sweeps away everything you must leave behind to move forward,” Jia Sung describes of the Death card in her Trickster’s Journey Tarot. Do you sense it, too, during these wild and unpredictable days of collapse, the voice that calls out for us to get in the boat together and keep rowing, even with no shoreline in sight?

We can cling to our comforts and coping strategies, to our fantasies, to certainty or hope or hopelessness, to ascension culture and to the entitlements we believe we deserve by some inexplicable and geographical birthright, even as we can no longer justify their ecological and human costs. We can tell stories about political saviors on “our side,” even as they scorch the earth for profit and sit unapologetically on thrones atop the mass graves of children. We can turn our backs to the extractive brutalities perpetrated against those outside of the sphere of our concern. We can blame and vilify “them” over there, you know, “those monstrous people” who no longer deserve our care, like the inmates we toss forever into irredeemable prison purgatory. Sure. We can… and remain inhospitable to the present tide that sweeps us, and its causes and conditions; inhospitable to the roots of suffering; inhospitable to Love; inhospitable to, yes, Grief.

Francis Weller calls this time the Long Dark. Generations shall pass “before we see the farther shore of this crisis, if we make it,” he wrote in a recent newsletter. (Can we let that in?) But Weller’s gift is his ability to see in the dark with a fierce clarity and an even fiercer grace, valuing the necessary and essential work — the “soul gestation” — that takes place there:

We meet a different self in this grotto of darkness, someone closer to the dream world and comfortable in shadowed places. This one knows about melancholy and hasn’t been swept up in the pursuit of the light. We need to know this other one who is more kindred with the nature of shimmering moonlight and soul than the brilliant sunlight of consciousness. This self sees through the layers of conditioning we all endure that oppress and domesticate. This one expresses something true and alive [...] in the tender intimacy of vulnerability.

— Francis Weller

From In the Absence of the Ordinary: Essays in a Time of Uncertainty

We are venturing, entirely together, towards the territory beyond the map, across the Sea of Disillusionment. And it must be so. Perhaps the appropriate thing to do is admit that we have nothing figured out, and perhaps that is beautiful, even joyous, in its way.

If words feel fragile and inadequate, if they are of little comfort these days, I understand. I know that many are feeling despair, especially since the US presidential election on November 5. Especially as we approach Inauguration Day, while fires of all-that’s-to-come engulf an intentionally uninsured and under-resourced Los Angeles. A challenging beginning to this new year. I understand. “Loss” is a necessarily destabilizing force, no matter what form it takes. Could I, I’d wave my wand and change all of it, if only to avert the suffering… alas.

Still, I have looked within and even as I touch into my wildest grief I do not find despair. What I find is a meaningful doorway — a dharma gate — to the cries of the world.

Like many, I read, I watch, I ache at every headline and image, and in anticipation of the increased suffering to come, especially (and always) befalling those who most need our collective care. Like many, I fear our boats may not reach the farther shore. But arising, too, is a strange relief, for now there are fewer places to hide from the painful realities already present — and here we are, standing at the edge, together. This soft vulnerability, our grief, could unite us.

Can we act on behalf of one another? And can we do that even when others refuse? Writing in the wake of the election results, Zenju Earthlyn Manuel offered this: “Many of us are more vulnerable than ever before. But in vulnerability we see that we are not alone and therefore more able to do what we must do to stay our freedom [...]. We have a long haul ahead of us.”

I long for the solidarity that comes from checking in and belonging to humanity and to all that holds us, rather than using our privilege to check out. The myth of our immunity and exceptionalism has caused a great deal of harm to ourselves and to the world, and has obscured our ability to see in the dark — and beyond it. Our binaries give no space for our contradictions. Our injuries are internal; the band-aids with which we have satisfied ourselves can’t heal our ailments. But crisis is an opportunity, a crack through which our increasingly disturbing political and societal reality can seize us from the slumber of indifference, the cult of “self-care,” the performance of blame.

“When we are standing at the edge, we cannot turn away from suffering, whether in our inner or our outer lives. There, we must meet life with altruism, empathy, integrity, respect, and engagement. And if we find the earth crumbling beneath our feet as we start to tip toward harm, compassion can keep us grounded on the high edge of our humanity. And if we do fall, compassion can harrow us (and beings everywhere) from the hells of suffering and bring us home,” Joan Halifax wrote in her book, Standing at the Edge: Finding Freedom Where Fear and Courage Meet. Her teachings sit within a Buddhist framework, but they reach for every single human heart. She would tell us now that we can endeavor to touch into our own basic humanity, to look at those who we consider to be reprehensible, those who we consider to be our enemies, even those who are engaging in harm. She would ask whether we are able to rehumanize them, to see if we can actualize a quality of inclusivity that is expressed through care — even as we speak out against their harms and seek accountability — in our practice, in our lives, in our relationships with all beings and things.

What could be more difficult? What could be more essential?

Put another way:

Is the natural order of things itself a miracle? How does the dying of someone you love fit into your idea of justice or mercy or compassion? How about when it is someone you don’t love? Here is where you find out what you really believe about what life is for, whether it is fair or just or worth the trouble.

— Steven Jenkinson

From How it All Could Be

We need to be willing to discard our illusions of being saved, our colonialist fetish for being right, our presumptive ownership over truth and justice — in favor of something more honest and compelling. We must be willing to move beyond the insistence that we might outrun our monsters should “our side” accumulate enough victories. The world is not a coagulation of villains versus heroes.

When we only know how to craft and externalize enemies, when we dictate what is “here” and what is somehow attainably “there,” when we claim mastery, we miss out on how the world churns, and then it slips away. For “here” can never be a singular location or idea, rather every “here” is a field of relational coherence, the way a single breath of oxygen is an entire orchestration involving our complex bodies, the sun, the photosynthetic processes of terrestrial and aquatic organisms, etc.

What we need, then, are spaces to welcome the intricacies, nuances, and failures; spaces of inquiry; spaces to grieve, to face what we all know is true and impossibly unsustainable. Truths that live in the water of Flint, Michigan; in the mineral mines of the Congo; in the prisons of America; in the pockets of ExxonMobil and Lockheed Martin executives; in the tattered tents of the unhoused and the refugees; in the garment factories of Bangladesh; in the terror-tainted milk of dairy cows and blood-soaked chambers of animal slaughterhouses; in the barrel of a gun that kills a CEO and a million denied healthcare claims; in the ruins of Gaza, Afghanistan, Iraq, Haiti, etc.

When we speak of our “interconnectedness,” do we not mean this, too?

We all insist that “our side” cares, but I often look around and am left to wonder, do we? In this fragmented, privatized, and predatory world, can we? Can we craft a new kind of politics, one of care and compassion, born of our collective vulnerability upon this “crumbling earth”? Is this not the very assignment we are hand-delivered by the Great Goddess, by Mystery, while in the throes of every single ceremony we do together? (This is what I wish for my ceremonial work to mean.)

“Love,” she tells us. Love as an act of deep listening. Love that knows Grief and says, “Yes, this too.”

For we are entangled and everything is in touch. Then here is what is true, in the always-stunning words of artist and visionary vanessa german: “We are the same that began the sky.” And this is a plea for the willingness to take up the assignment of our days; this is a plea for turning towards the Love and the Grief of our world, for witnessing and feeling it, for tending it.

In a dream I asked him

what can I do

if I can’t change itand he pointed

to the graves

and whispered witness it.— Joseph Fasano

“Rumi”

Look, with a gentleness in your soul. For the beauty and the bewilderment that might be touched when we drop our manic pursuit of “healing” and actually let our brokenness give way to new forms of recognition and care. After all, as Francis Weller has taught me, the opposite of emptiness is not fullness, rather it is embeddedness, participation, intimacy. Or, as Zenju Earthlyn Manuel wrote, “The way to our liberation is to forge, with our heat, all that is broken in this country into a kind of freedom we never imagined we had the power to shape.” It is not a freedom conferred by force, by might, by external circumstances, or by the reign of Reds or Blues. We won’t find it in a New-Year-New-You workshop. Nor does it rest upon hope, for, as Báyò Akómoláfé always reminds us, hope is not an answer to our yearnings.

Remember the shrew, I hear. Not one of us is getting out of this. And as my brilliant friend Nirmala reflected last month as we exchanged philosophical voice memos after her father’s death, “For every single one of us, our lives, whether consciously or unconsciously, are an offering on the altar.” We can honor this fact, not in rising to the occasion, but, like the shrew, by burrowing in: “The very root of the word ‘occasion’ is the Latin ‘cado,’ which means ‘fall.’ Our grace is not ascension but collapse, the collapse of all our effort, all our seeking,” poet Fred LaMotte inspires.

We might move towards the Long Dark with our hearts available to beauty and pain. This possibility fills me with a wild and irreverent joy; the joy of imagination, creativity, and aliveness; the joy that seeps through the cracks of brokenness; the joy born of our willingness!

As our treasured elder and torch-bearer Joanna Macy tells us, “The refusal to feel takes a heavy toll. Not only is there an impoverishment of our emotional and sensory life, flowers are dimmer and less fragrant, our loves less ecstatic, but this psychic numbing also impedes our capacity to process and respond to information. The energy expended in pushing down despair is diverted from more creative uses, depleting the resilience and imagination needed for fresh visions and strategies.”

Our losses are opportunities — for growth, for art, for prayer. Affirmed in the prayer I hear again the voice of vanessa german: “All seeds break open to bring forth. Everything begins from a breaking place.”

My friends, life will bloom from this corpse.

And grief tending can be our compass. It is how we can address our hungry ghost legacy of emptiness. I said it in May, if not every time I write to you: If only we could collectively fall to our knees in tender and humble grief, for I believe it is the vulnerability of a broken heart that can truly know what it is to choose to love. Not conceptually, but enacted through an honest assessment of our choices and behaviors, through accountability and acknowledgement of our own dualities… and our own eventual demise.

For now, I send my blessings for a beautiful and radical 2025, a year that nourishes as much as it pushes us. A year of grace and gratitude. Ceasefire everywhere. Abundant sunshine, abundant rain, abundant peace. Wellness in every heart. And forever, forever, forever, collective liberation.

I’m taking these cold, still, quiet days of winter to listen. We are unraveling, we feel it — and I am rapt. I look out and the Sea of Disillusionment is yet shimmering and mesmerizing; its waves are neither “here” nor “there,” but destinationless and relational; it is a messy and chaotic symphony of being itself — by losing itself and becoming other.

Let us set sail. ♥

What

To make of falling apartness?

What

To do

To feel

To have

Too many wants

I’m afraid

In this falling apartness

A hollowing out

Of what we thought

Believed

Hoped

So amazingly from all sides

The Right

And

The Left

All sides unexpectedly

Caught beyond guard

Rails falling

In this apartness

All sides!

Ah

Some thing stirs

In this one possibility

The rising

As in yeast

Dormant

Until spit upon

With a bit of sugar and warm water

Something stirs

When no thing

Absolutely

No thing

Works

Something stirs

If

And only if

We see what cannot be seen

And hear what cannot be heard

A stance unfolds

A threshold appears

What?!— Norma Wong

From When No Things Works: A Zen and Indigenous Perspective on Resilience, Shared Purpose, and Leadership in the Timeplace of Collapse

Thank you as always for your poetically powerful and inspiring words.

Thank you for this buoyancy of intellect that keeps me hoping, dreaming & being present. Much love dear friend!